SPINAL CORD EPENDYMOMAS

SPINAL CORD EPENDYMOMAS

Ependymomas are believed to account

for 60% of all primary neoplasms of

the spinal cord and filum terminale.

Intraspinal ependymomas are most

easily grouped into 3 classes:

intramedullary lesions,

myxopapillary ependymomas, and

metastases from an intracranial

origin.

Preferred

Examination

Preferred

Examination

The initial imaging evaluation

likely includes plain radiography of

the spine. The images may

demonstrate erosion of the pedicle

or scalloping of the dorsal

vertebral body surface. However, the

yield of plain radiography is

limited, and when clinical suspicion

exists, MRI of the spine with and

without gadolinium enhancement is

the study of choice. MRI permits

evaluation of the cord substance

itself for masses and associated

findings such as edema, hemorrhage,

cyst, syringomyelia, and cord

atrophy.

For myxopapillary tumors, both the

brain and spine should be evaluated

with MRI, with and without

gadolinium enhancement. Solitary

intramedullary lesions are less

frequently associated with

intracranial spread; thus, cerebral

imaging is less important.

Myelography may assist in localizing

an intraspinal mass to the

extradural, intradural

extramedullary, or intradural

intramedullary compartments. A

centrally situated, regularly

fusiform cord may be suggestive of

an intramedullary ependymoma,

whereas fusiform swelling in the

cauda equina, particularly when it

is large enough to result in bony

erosion, and a blockage of contrast

enhancement may be consistent with

an ependymoma of the filum.

With a yield similar to those of

plain radiography or myelography,

computed tomography (CT) scan

findings are not conclusive for

ependymoma. Nonspecific findings of

canal widening, bony erosion, and a

thickened cord or filum are

suggestive but not diagnostic of

ependymoma.

Radiography:

Radiography:

The radiographic diagnosis of

intraspinal tumors is indirect and

nonspecific. Changes induced by the

tumor may be observed in the

adjacent tissues on plain films. The

pedicles may appear eroded,

flattened, or concave, with an

increased interpedicular distance as

a result of chronic pressure

resulting in bony atrophy.

Similarly, scalloping of the

posterior part of the vertebral

bodies or thinning of the lamina

with a widened spinal canal may be

observed. Scoliosis may be visible

on plain radiographs. Finally, in

rare cases, intratumoral

calcification may be observed on

radiographs. Because of the limited

yield of plain radiography, when

clinical suspicion exists, MRI of

the spine with and without

gadolinium enhancement is the study

of choice.

MRI:

MRI:

On T1-weighted images, ependymomas

generally appear isointense relative

to the normal cord, although they

may appear hypointense (a less

common finding). Heterogeneity and

hyperintensity on T1-weighted images

may indicate a hemorrhagic component

of the mass. On T2-weighted images,

ependymomas are generally

hyperintense relative to the normal

cord. Ependymomas are homogeneously

and intensely enhancing with the

administration of a gadolinium-based

contrast material. With contrast

enhancement, the tumor often is seen

to have well-defined borders.

Hemosiderin

Hemosiderin

Hemorrhage or hemosiderin in or at

the cranial or caudal margin of

ependymomas is a common imaging

finding. T2-weighted MRIs may

demonstrate a low-signal-intensity

rim around some tumors; this finding

represents the hemosiderin. In 1995,

Fine et al noted this finding in

only 20% of tumors; this percentage

is far lower than the 64% Nemoto et

al reported in 1992.] This

hemosiderin cap is fairly suggestive

of ependymomas. With filum

ependymomas, hemorrhagic products

may be seen within the filum.

Cysts

Cysts

In 1995, Fine et al observed that 1

of 25 tumors evaluated was cystic,

but 14 had associated reactive

cysts: 11 cysts were rostral to the

tumor; 10, caudal to the tumor; and

7, both rostral and caudal. All

reactive cysts had signal intensity

similar to that of CSF. The cysts

were hypointense on T1-weighted MRIs

and hyperintense on T2-weighted

MRIs. These cysts did not enhance

with the administration of contrast

material. In 1995, Wippold et al

examined 20 patients with

myxopapillary ependymomas; of these,

3 had cystic tumors, and 2 had a

syrinx. Rarely do the tumors

themselves have a cystic appearance.

Tumor size and location

Tumor size and location

Cervical lesions average 4.2

vertebral segments in length,

thoracic lesions average 3.1

segments, and filar tumors average

4.0 segments. Most often,

intramedullary ependymomas occur in

the cervical cord; fewer lesions are

thoracic, and fewer still occur at

the conus. About 50% of intraspinal

ependymomas occur at the cauda

equina (see the image below); these

are predominantly of the

myxopapillary subtype. Multiple

lesions occur much more often in

this region, with a frequency of

15%.

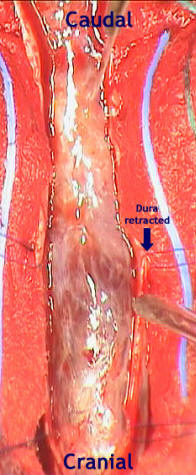

T2-weighted magnetic resonance image

demonstrates a myxopapillary

ependymoma in the cauda equina and

the lesion after dural opening.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The chief intramedullary lesions

from which ependymomas must be

distinguished are astrocytomas and

hemangioblastomas.

Ependymomas of the filum must be

distinguished from schwannomas,

hemangioblastomas, and astrocytomas.

Astrocytomas of the cord are

infiltrative and have margins that

are less sharp than those of the

other lesions. Astrocytomas are less

prone to hemorrhage and infrequently

result in a hemosiderin cap. More

often, astrocytomas are eccentric in

location. Schwannomas may

demonstrate a central area of poor

enhancement.

Hemangioblastomas have prominent

vascularity, as well as large

reactive cysts, which are consistent

with their intracranial appearance.

With MRI, signal intensity

characteristics of hemangioblastomas

are similar to those of ependymomas.

The tumor nodule, which is situated

on a pial surface, may have more

intense enhancement than that of

ependymomas. Local edema of the cord

is more impressive around

hemangioblastomas than ependymomas.

Flow voids are often visible in

hemangioblastomas.

It may be impossible to distinguish

schwannomas from filum ependymomas;

their signal intensity

characteristics are very similar. In

fact, the signal intensity

characteristics of schwannomas and

ependymomas are nearly identical on

T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and

gadolinium-enhanced MRIs.

Schwannomas more often assume a

dumbbell configuration and result in

an enlargement of the adjacent

neural foramina. When the tumors are

small, the observation of an origin

from a root in the cauda equina,

rather than the filum, may aid in

distinguishing schwannomas from

myxopapillary ependymomas. The

distribution of the roots of the

cauda equina in the thecal sac may

help in distinguishing the tumors:

An ependymoma of the filum pushes

the roots to the periphery of the

thecal sac, whereas a schwannoma of

the cauda more often pushes the

roots together in an eccentric

fashion.

Compared with ependymomas,

schwannomas infrequently appear

multilobulated. The periphery of

schwannomas is strongly enhancing,

but the tumors may have central

areas with poor enhancement.

Note on gadolinium

Note on gadolinium

Gadolinium-based contrast agents

(gadopentetate dimeglumine

[Magnevist], gadobenate dimeglumine

[MultiHance], gadodiamide

[Omniscan], gadoversetamide

[OptiMARK], gadoteridol [ProHance])

have been linked to the development

of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis

(NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing

dermopathy (NFD). The disease has

occurred in patients with moderate

to end-stage renal disease after

being given a gadolinium-based

contrast agent to enhance MRI or MRA

scans.

NSF/NFD is a debilitating and

sometimes fatal disease.

Characteristics include red or dark

patches on the skin; burning,

itching, swelling, hardening, and

tightening of the skin; yellow spots

on the whites of the eyes; joint

stiffness with trouble moving or

straightening the arms, hands, legs,

or feet; pain deep in the hip bones

or ribs; and muscle weakness.

Treatment:

Treatment:

Surgical

resection is the choice and it is

limited with the invasive character

of the tumor, but the exophytic

parts can be removed and it is

preferable to use neuronavigation to

avoid damage to the neural

structures. Radiotherapy must

follow with all stages of the

ependymoma.

For

demonstration for a case with filum

terminal ependymoma with exophytic

growth down the cauda equina case

click here!

|